Thursday 5th May might have been a significant date in the calendar for Scottish politics, but more importantly it was also the date of our Knowledge Exchange Forum in Inverness. The event invited an audience of social enterprise practitioners, academic researchers and associated organisations to share their thoughts and ideas of social enterprise and its links to health and wellbeing.

The forum included fantastic presentations from 3 local social enterprises; Calman Trust, Highland Blindcraft and Eden Court; alongside presentations from NHS Highland and the Highland Council. The event also allowed us the opportunity to discuss in groups what we mean by health and wellbeing, how our work might affect the lives of others, and how this might be measureable, leading to some thought provoking insights! As there were so many interesting points raised we have asked our CommonHealth team to highlight just a few……

A massive thank you to everyone who attended and shared their views, and a special mention to the Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) for their support and input!

Working as a social enterprise

The presentations from Calman Trust, Eden Court, and Highland Blindcraft reflected the diverse ways in which social enterprise has become both a structure -around which you can build an organisation- and a tool -which third sector organisations can make use of to fulfil their social missions. For example Calman Trust operates the social enterprise Ness Soap and Cafe Artysans; Eden Court is a publically funded arts organisation that uses elements of social enterprise in its practice; Highland Blindcraft has existed in one form or another for 140 years. Currently it operates as a charity limited by guarantee and has been variously labelled a social enterprise, and a supportive business.

People and organisations who want to create social change and generate social value don’t worry too much about what they’re called. For many organisations, if ‘social enterprise’ is a title which might bring in funding to help their users, then they’ll happily slap ‘social enterprise’ stickers on everything. But equally, if the funding flavour of the month is ‘social business’ or ‘charity’, then that’s the name they’ll use. Participants’ commitment to their social purpose was prioritised over the label used to describe their work.

This raises questions for academics like us at Commonhealth, and suggests that we should perhaps think of social enterprise as a set of processes that organisations use, rather than a group of organisations that share common characteristics. In turn this leads to further questions for policy makers and the support that should be in place for social enterprise.

For those of you interested in this discussion you may be interested in Simon Teasdale’s upcoming professional lecture:What’s in a name?

Addressing vulnerability and providing support

Several of the discussions throughout the day picked up on concerns that practitioners were witnessing increased levels of vulnerability, especially in connection to young people and youth unemployment. In this context the imperative to balance the ‘business’ elements of a social enterprise with its social purpose, becomes an ever more delicate balancing act; and for some this was likely to become a central challenge for the sector in coming years. Social enterprises therefore felt that while they could not hope to solve all the problems they faced, they could help to make young people more resilient and able to cope with the challenges they faced in the future.

When discussing support and vulnerability, often what can be neglected are the effects that social enterprise activity might have on its founders, board members and managers. When individuals volunteer their time and energy into creating and building their social enterprise we can forget to consider the impact that this might have on their personal and family life, and the sacrifices that they have to make. This can be in terms of personal finance, lack of time spent with loved ones and having to work long and anti-social hours to make things work. Yet support for such groups can be scarce.

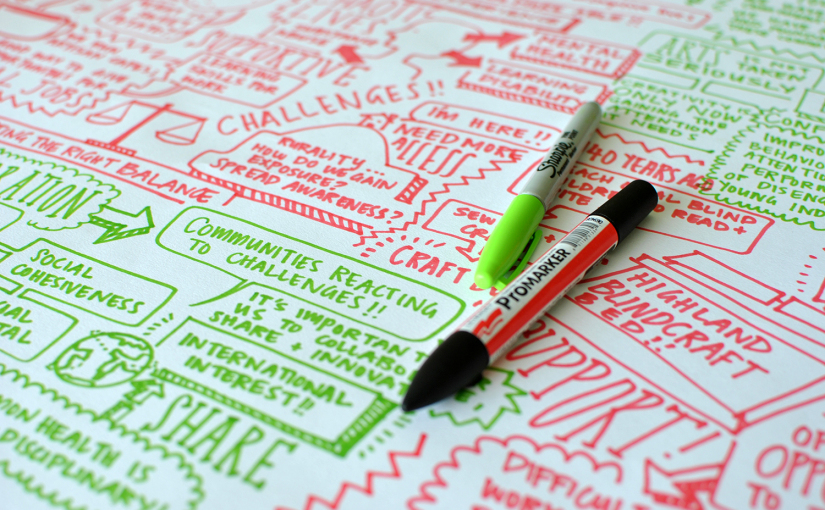

Amazing illustrations by Sarah Ahmad

From pathways to evidence

Social enterprises frequently need to prove (or attempt to) the outcomes of their work. Practitioners from the numerous organisations in attendance could relate to us the pathways that individuals had taken through their organisations, but often felt that these stories alone were not taken seriously as evidence of their impact on health and wellbeing.

Often the most small and subtle changes were felt to be the most powerful. In environments where social enterprise practitioners are working every day, the most satisfying aspects might be simply putting a smile on a young person’s face. Yet, not only is it difficult to measure the value of a smile, it may not be what funders are interested in anyway. There are ways of measuring impact (e.g. SROI or Social Audit) which may give a snapshot of the social value of a social enterprise. However, such measurement can be tough when funders want hard numbers not stories, or can’t think about long-term outcomes beyond the funding period.

Moreover, what was commonly found was that measures do not always account for major differences in social enterprise type and scale. For example, a community centre might benefit 1,500 community members, yet a childcare service might only benefit 5; and each activity impacts to a variety of different levels. Therefore, how can measures be truly representative of how people are individually affected?

Taking all of these insights into consideration we have a lot to keep us busy until the next event!

Gillian Murray, Bobby Macaulay, Danielle Kelly, Clementine Hill-O’Connor, Fiona Henderson, Steve Rolfe