Recently I’ve been struck by the number of TV programmes gracing our screens that have been dubbed ‘Poverty Porn’. The premise of shows such as Benefits Street and The Job Centre seems to be that there is a whole section of the population who are ‘scroungers’ and ‘skivers’, who choose to be out of work and reliant on benefits and therefore deserve the scrutiny of the television lens. This is in contrast to the rest of us who are in work and ‘strivers’ who are obviously part of hardworking families we’ve heard so much about in the past few months.

Work has been extolled as the solution to poverty by a variety of politicians including Iain Duncan Smith who claimed: ‘In improving people’s prospects, the evidence has always held that work is the best way for individuals to lift themselves and their children out of poverty.’ (Full speech available here)

In fact the sheer volume of governmental reports relating to unemployment and the need to get people off benefits and into work is overwhelming. As I write up my PhD and reflect on the experiences of those I have worked with I’ve been thinking about what we mean by work and what we think, or want, it to do for us.

Moving away from the financial claims made by those touting the value of work (which have been questioned and critiqued here), the themes emerging from my research with the CommonHealth project has made me start to think through some of the health implications surrounding the issue of employment and quality of work .

A report from the DWP found that:

‘Work can be therapeutic and can reverse the adverse health effects of unemployment. That is true for healthy people of working age, for many disabled people, for most people with common health problems and for social security beneficiaries. The provisos are that account must be taken of the social context, the nature and quality of work, and the fact that a minority of people may experience contrary effects.’

Of interest here is the question of the ‘nature and quality’ of work and what might contribute to work that can be considered therapeutic.

The implication in the report is that it is paid work that can offer solutions to the negative health effects of unemployment. But some of my early findings suggest that the value of work and its effect on health is less related to the payment of wages and more in the satisfaction of producing something, offering a service to someone and getting positive feedback on something you have achieved.

Lorna (one of my research participants) told me about the others things, beyond money, that she gets out of her involvement with the group: ‘I’ve never had a wage from it but there are other rewards like when you finish a product and someone says ‘Oh that’s great I want to buy that!’’. Jo described to me how good it felt to run an informal lunch club and know that people enjoyed and valued the service she gave. Stacey valued the activities in her group as something that gave her a rest from the other worries in her life; she said, ‘If you’re busy doing something you relax more’.

This kind of informal (and unpaid work) is not only of benefit to those involved but also to their families and communities who will benefit from the provision of certain services and a potentially more relaxed home life. In Oxfam Scotland’s work on the HumanKind Index they found that one of the factors people ranked as most important to their quality of life was ‘satisfactory work (paid or unpaid)’.

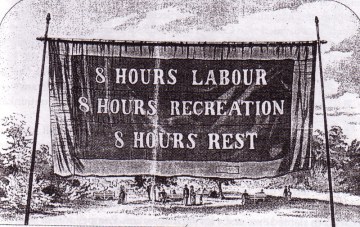

The distinction that we need to draw here is that the kind of short-term, low paid work offered to people on unemployment benefits is not the kind of work associated with the therapeutic benefits identified in recent research. Much of the paid work currently on offer may not deliver an acceptable standard of living, yet it is still held up as the ideal activity for all in society. With this in mind it is important to question what other purposes it serves and what, in an ideal world, we want work to look like.