My first knowledge of Muhammad Yunus was when I was given his first book, Banker to the Poor in my second year of university. It managed to combine my previously irreconcilable beliefs in the power of small businesses and the need to help the poorest in society through an elaborate yet practical description of the mainstreaming of microfinance provision as a non-state solution to poverty. I had a bit of an identity crisis in considering whether I should continue with my politics degree or start again with business and economics but instead tried to include microfinance in everything I did. This culminated in incorporating social enterprise into my final dissertation by considering its ethos and processes in relation to Marxist theory, under the title: “Right-Wing Means to Left-Wing Ends: Can Social Business Achieve the Goals of Marxism in the Modern Capitalist Economy?”

This question arose in more ways than I had ever conceived of a couple of weeks ago when I presented a paper at the academia conference of the Global Social Business Summit which was held, very appropriately, at perhaps the most poignant meeting place of ‘right’ and ‘left’- Berlin. The summit, now in its 7th year, was the brainchild of Yunus and is one of the biggest events in the social business calendar.

Our conference venue was the former East German government building, beautifully adorned with mosaics of the revolution, red-flag-waving workers, functioning industry and smiling families. The building is now home to The European School of Management and Technology (ESMT), a business school which specialises in executive education programmes. This irony was not lost on the school as they took pride in the tiled mosaic of the ‘hammer and compass’ which towered over the laptop-strewn lecture theatres teaching profit-maximisation strategies. I felt even Checkpoint Charlie struggled to match up to that collision of cultures.

The summit itself continued this juxtaposition with corporate CEOs and Syrian musicians alike speaking of the ‘double bottom line’ of economic and social returns to the assembled company of academics, social entrepreneurs, corporate ‘high heid-yins’ and idealistic young people in an abandoned airport hangar. This meeting of very well paid minds took place in Hangar 7 of the former Tempelhof airport, where you could buy an ethical glass bottle for €25, while the other hangars were apparently being used for the temporary housing of Syrian refugees.

I don’t know whether these parallels and juxtapositions are impossible to avoid in Berlin, or just served as a constant reminder of the clash of cultures engrained in social enterprise, which it could be argued are the very reason for its success. There is a line in Banker to the Poor where Yunus says that when he was setting up the Grameen Bank he was criticised by the Far-Left in Bangladesh for ‘removing the revolutionary zeal’ of his borrowers by giving them just enough that they didn’t want to risk it. He saw this as a good thing, that he was mitigating against the detrimental forces of the market to the extent that people didn’t need to resort to armed rebellion and top-down reorganisation.

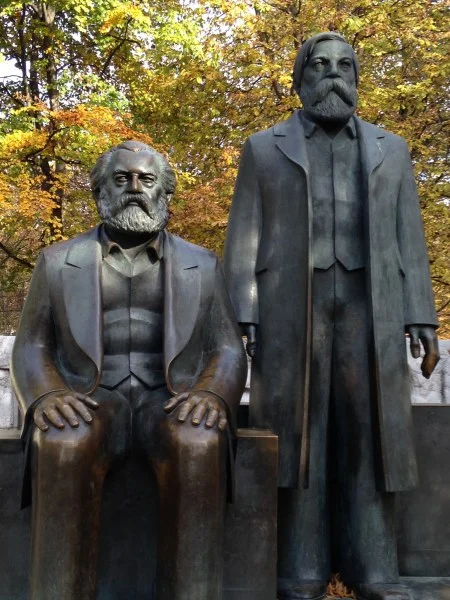

One can only guess what these two might have had to say about that.